What Is Active Recall? Does It Work Better Than Rereading Notes?

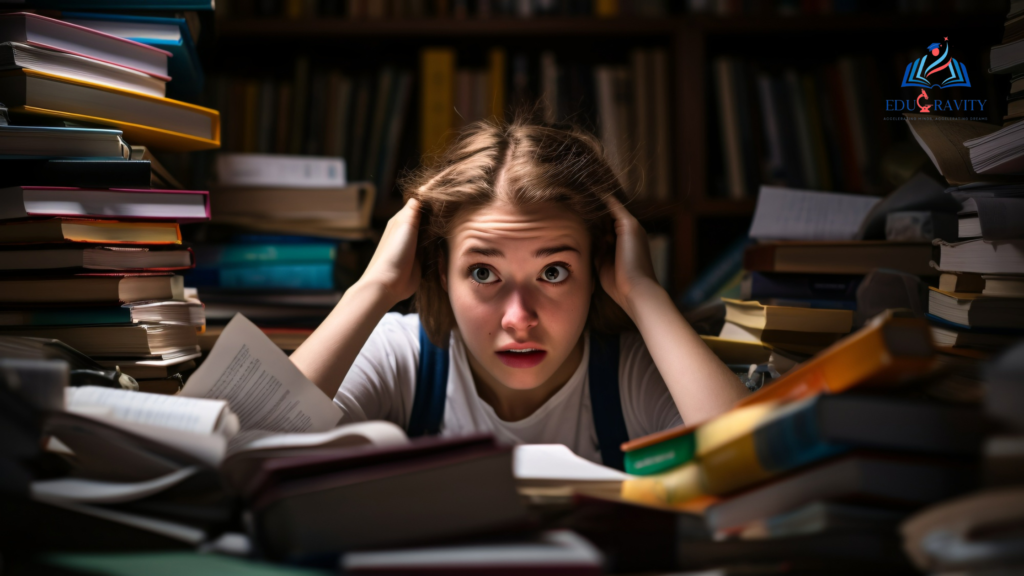

Most students have spent hours going over their notes the night before an exam, convinced that if they just read through everything one more time, it’ll stick. It feels productive. It’s familiar. And in most cases, it doesn’t work nearly as well as they think it does. Active recall is the thing that actually does work. Here’s what it is and why the difference matters.

What’s covered in this article

What Active Recall Actually Is

Active recall is the practice of retrieving information from memory rather than looking at it. Instead of reading your notes and letting the information wash over you, you close the notes, ask yourself a question, and try to answer it from scratch. That moment of struggling to pull something out of your memory, that’s the bit that matters.

The name sounds technical but the idea is simple. Flashcards are active recall. Practice questions are active recall. Closing your textbook and writing down everything you remember about a topic before checking is active recall. Any time you’re forcing your brain to produce information, rather than just recognise it, you’re doing it.

Rereading is the opposite. You look at information that’s already in front of you. There’s no retrieval. Nothing is being pulled from anywhere. The information goes in, briefly, and then tends to fade much faster than most people expect.

The simplest version: Read a section of your notes. Close them. Write down everything you can remember. Open them again and check what you missed. That’s active recall. You can start doing it tonight.

Why Rereading Feels Like Studying But Often Isn’t

Here’s the thing that trips people up. When you reread your notes, you recognise the information. And recognition feels like knowledge. You look at a definition and think, “yes, I know that.” You look at a diagram and think, “yes, I remember covering this.” But recognition and recall are very different things.

I’ve seen this play out with students preparing for exams. They spend three hours going over their Chemistry notes, feel confident, sit the paper, and then can’t structure an explanation from scratch because the exam doesn’t show them the notes first and ask if they recognise them. It asks them to produce the information. That’s a fundamentally different cognitive task.

There’s also something called the fluency illusion, which is the feeling of understanding that comes from reading material that’s been seen before. Familiar language reads more smoothly. Familiar concepts feel more obvious. The brain registers this smoothness as competence. It mostly isn’t. It’s just familiarity. And familiarity fades quickly when the exam paper is blank and you have forty minutes to fill it.

This isn’t a character flaw. It’s how passive learning works. The problem is that students keep choosing it because it feels less uncomfortable than the alternative.

What the Research Actually Says

The evidence here is pretty consistent, and it’s been building for decades. A well-known study by Roediger and Karpicke in 2006 found that students who studied a text and then tested themselves on it performed significantly better on a final test a week later compared to students who simply restudied the material. Not marginally better. Substantially better.

The mechanism behind this is sometimes called the testing effect or retrieval practice effect. When you try to recall something and succeed, that memory becomes stronger. When you try to recall something and fail, then check the answer, you actually remember it better than if you’d just reread it. The struggle, even an unsuccessful one, does something useful. It signals to your brain that this piece of information matters.

Birmingham City University’s guidance on revision echoes this directly, recommending retrieval practice as one of the most evidence-backed approaches available, precisely because it encodes information more deeply than passive review.

None of this means rereading is useless. Reading is how you initially learn material. It’s the first pass. The problem is when rereading becomes the only strategy, repeated over and over, substituting for the harder work of actually testing yourself.

How to Use Active Recall in Practice

The good news is that you don’t need special equipment or software to do this. You need your notes, a piece of paper, and enough discipline to close the notes before you start writing.

The blank page method

This is probably the most accessible version. After studying a topic, take a blank sheet of paper and write down everything you can remember about it. No peeking. When you’re done, compare what you’ve written to the actual material. The gaps you find are exactly what to focus on next.

Some students find this uncomfortable. Good. That discomfort is the signal that retrieval is happening. It tends to fade as the material becomes more secure in memory.

Flashcards, used properly

Flashcards are probably the most common active recall tool. But there’s a right way and a less effective way to use them. The right way involves genuinely trying to answer the question before flipping the card, not just reading the front and immediately checking the back. That intermediate step of actually attempting to produce the answer is where the learning happens.

Apps like Anki automate this well. They use spaced repetition to surface cards at the right intervals, which pairs very naturally with active recall. But a stack of physical flashcards works too. The tool matters less than the habit.

Practice questions and past papers

For students preparing for formal exams, practice questions and past papers are probably the highest-value form of active recall available. They mirror the actual exam format, they require you to produce rather than recognise information, and they reveal exactly where your understanding breaks down.

The important thing here is not to use past papers as a reading exercise. Sit them under exam conditions, or as close to it as you can manage. Time yourself. Write full answers. Then mark your own work against the mark scheme and be honest about what you got wrong and why.

Teaching it to someone else

If you can explain a concept clearly to someone who doesn’t know it, you understand it. If your explanation gets tangled or you find yourself saying “you know, the thing where…” then you don’t understand it as well as you thought. This is sometimes called the Feynman technique. It’s essentially active recall in conversation form.

A practical starting point: Pick one topic you’ve recently covered. Close everything. Set a timer for ten minutes. Write down everything you know about that topic. Then check. Whatever you missed, study those parts again. Do this for every topic you’re revising. It sounds simple because it is. Most of the best study strategies are.

Combining Active Recall With Spaced Repetition

These two techniques were made for each other. Active recall is about how you study. Spaced repetition is about when. Used together, they’re more effective than either alone.

Spaced repetition works on a simple principle. You remember things better when you review them at increasing intervals rather than cramming them all at once. If you learn something on Monday, review it on Wednesday, again the following Monday, then two weeks later, you’re much more likely to retain it than if you spent six hours on it on Sunday night.

The reason it pairs well with active recall is that it forces you to retrieve information at the moment you’re most at risk of forgetting it. That’s the exact point where retrieval is hardest and, as a result, where it does the most good. You’re not reviewing things you already know well. You’re targeting the edges of your memory, the places where things are just starting to slip.

Apps like Anki handle this automatically using an algorithm that tracks how confidently you recalled each card and schedules the next review accordingly. It takes some setup, but once your decks are built, the system manages the timing for you.

Common Mistakes Students Make With Active Recall

A few patterns come up again and again that limit how effective this technique actually is.

The biggest one is peeking too soon. Students flip the flashcard after two seconds of thought rather than sitting with the discomfort of not knowing. The struggle is the point. If you immediately check every time you’re unsure, you’re undermining the whole process.

Another is only using active recall for facts. Definitions, dates, formulas. Those are the easiest things to practise with flashcards, but many subjects require you to apply knowledge rather than just state it. For those subjects, practice questions and essay-style answers are a better fit. A History exam won’t ask you to list causes of World War One. It’ll ask you to analyse them, weigh them, argue a position. Practising that kind of extended response is its own form of active recall.

A third mistake is saving it for the end. Active recall is most powerful when used throughout the learning process, not just in the final week before an exam. If you test yourself on material shortly after first encountering it, you encode it more deeply from the start. Revision then becomes a strengthening exercise rather than a rescue operation.

Is Active Recall Right for Every Subject?

Pretty much, yes. Though the form it takes varies.

For content-heavy subjects like Biology, History, Economics, or Geography, flashcards and the blank page method work well. There’s a lot of information to retain, and retrieval practice is excellent at building that kind of knowledge base.

For Mathematics and the sciences, the equivalent is working through problems without looking at worked examples. If you can solve a problem from scratch, you understand the method. If you can only follow along with someone else’s solution, you’re recognising, not recalling.

For English Literature, the closest equivalent is writing essay plans and argument structures without referring to your revision notes. Practising how you’d argue a point, which quotes you’d use, how you’d structure a response. Those are retrievable skills, not just facts.

There’s no subject where “just reread your notes more” is the optimal approach. But the specific form active recall takes does vary, and it’s worth thinking about what the actual exam requires and practising that specific skill.

Helping your child study smarter, not just harder?

At Edugravity, we work with students across Sharjah and the UAE in small groups of no more than 6. Our tutors build active recall into every session, so students are practising retrieval from day one, not just reviewing material and hoping it sticks. Whether it’s IGCSE, A Levels, or any other curriculum, we can help.

WhatsApp Us Book Free DemoFree diagnostic session available. Not sure where to start or which subjects need the most attention? Come in for a free assessment. We’ll give you an honest read on where things stand and what a realistic revision plan looks like. No pressure. Book yours here.

Key Takeaways

- Active recall means retrieving information from memory, not just looking at it. Closing your notes and trying to write down what you know is the simplest version.

- Rereading creates familiarity, not knowledge. The fluency illusion makes it feel like learning when it mostly isn’t.

- The research is consistent: students who test themselves perform significantly better than those who reread, even when total study time is the same.

- Practical methods include the blank page technique, properly-used flashcards, past papers under timed conditions, and explaining concepts out loud.

- Pairing active recall with spaced repetition, reviewing material at increasing intervals, produces the strongest long-term retention.

- The mistake most students make is leaving active recall for the final week. It works best when used throughout, from the first time you encounter new material.